Mutanabbi Street: Baghdad’s Cultural Heartbeat, Beyond Books

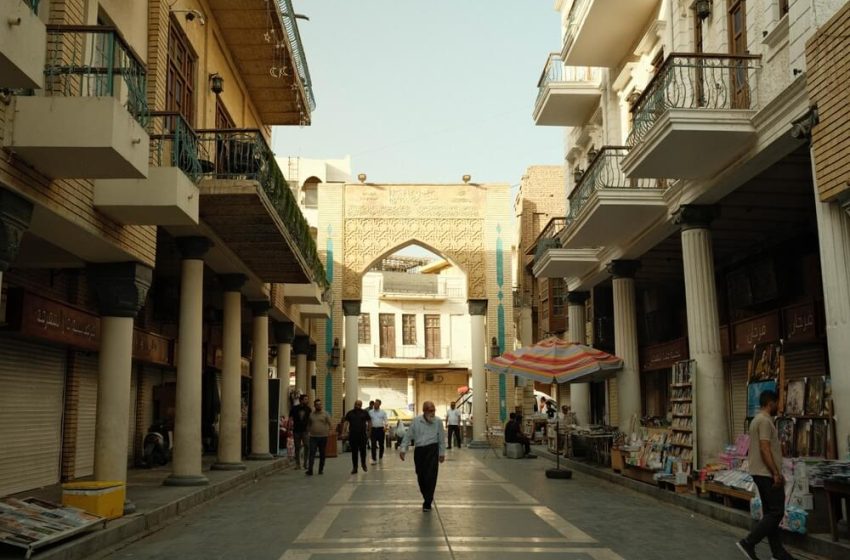

Baghdad’s Al Mutanabbi Street.

Baghdad (IraqiNews.com) – In the heart of the capital, Baghdad, at about 700 metres long, and extends between Al-Rashid Street and the eastern bank of the Tigris River stands Mutanabbi Street, among the city’s oldest thoroughfares—a historic haven pulsating with cultural resonance. Its literary legacy, harking back to the Abbasid era, brands it a cultural gem for Baghdad. With time, Mutanabbi Street metamorphosed into a bastion of intellectual liberty, drawing in writers, artists and tourists from across the country.

Strolling down the street, one encounters an array of book and art shops. Among them, an eclectic selection of tomes—from timeless classics to novels and poetry collections, some with histories stretching back a century. These aren’t merely bookstores; a more fitting descriptor would be museums. Each stall, a curated repository, a personal exhibition of books amassed by dedicated owners. Take Abu Fatima, a custodian of a literary museum. His mind, a catalogue, effortlessly recalling the essence of Foucault, the depth of Dostoevsky, and the brilliance of Qabbani—all at the tip of his tongue.

Away from the book stalls, it’s become a hub for creativity. Readers, artists, and thinkers convene in the cafés along the street, delving into conversations, exchanging ideas about the world and literature. Poetry recitals, book festivals, and cultural affairs unfold on Mutanabbi Street, pulling people from every path of life who revel in the power of the written word.

Embedded in this artistic hub is the historic architecture, a mirror to Baghdad’s protracted and intricate past. Al-Mutanabbi Street was named after the prominent poet Abul Tayeb al-Mutanabbi, who lived during the 10th century and was born in what would become modern-day Iraq during the Abbasid dynasty. King Faisal I officially opened the street in 1932. The architecture contributes to the magnetic pull of Mutanabbi Street, forging an atmosphere that merges the old with the new.

At the street’s corner stands Al Shahbandar cafe built in 1917. Its weathered facade, bearing the scars of years gone by, serves as a canvas for the history of Iraq and the myriad tales spun by its visitors. For over a century it served as a hub for community chatter, political debates, and a shared appreciation for the arts and social thought. Inside, the air is thick with the heady embrace of smoke, swirling and dancing in homage to countless conversations. This ancient cafe, a silent witness to the soul of Iraq, stands as a living archive of its history and a shelter for those seeking to savour the richness of tradition.

The street came to an abrupt pause in 2007, disrupted by the blast of a car bomb. Four sons and the grandson of the Shahbandar Café owner, Mohammad Al Khashali, lost their lives that day, their portraits hanging stoically greeting you at the entrance. Still, the café remains ever full, livelier than before. It stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of the Iraqi people amid the tumult of social and political events.

Just beneath Mutanabbi Street’s warmth and cultural weight lies a profound symbol of resilience. From the birth of the nation through the collapse of its monarchy under Saddam Hussein’s regime, to the US-led invasion, and the tragic burning of the ‘Al-Nahda’ library housing invaluable religious and legal books, as well as the car bombings that scarred the street—amidst the unending turmoil of political unrest, Al Mutannabi stands.

“It is the capital of Baghdad. Though its length does not exceed one kilometre, it represents a national identity, a comprehensive legacy, and a cultural and historical dimension,” says Mustafa Al Hashem, a devoted visitor to Al Mutannabi.

“The bombing and unrest were unable to destroy the spirit of culture and thought that the street represents, as it is considered an important cultural symbol. This place isn’t just a social hub; it’s the very arena where opinions and ideas clash and meld, a sanctuary for discourse. Beyond its social function, it wields political significance—a forum to voice dissent, a rallying ground for those who’ve historically clamoured for political reform,” Al Hashem continues.

During the Tishreen protests of 2019, as citizens took to the streets demanding political reform and economic improvements, Mutannabi Street emerged as a haven for dissidents—political thinkers, philosophers, and activists gathered openly to discuss and rally support for the desired political changes. As you wander the alleys, a deliberate feature becomes apparent in its design—an enclave meticulously crafted for intellectual and political discourse, adorned with circular seating reminiscent of miniature patios, strategically placed. Each of these spaces is marked by a sign, proudly indicating the focal point of discussion.

In a nod to the 17th-century French salons, these social gatherings are designed to foster intellectual exchange and spirited debate. Within Iraq’s dynamic transformation, avenues resembling Baghdad’s Mutanabbi Street are emerging across the nation. These vibrant centres of social and cultural vitality stand as custodians of Iraq’s spirit. Beyond safeguarding and elevating them, it becomes imperative to encourage their development in every province.

To echo Al Hashem’s poignant sentiment: “Al-Mutanabbi is the heart that pumps us with love and knowledge; it is the third river of Iraq, irrigating its children with the lifeblood of knowledge, culture, and freedom.”